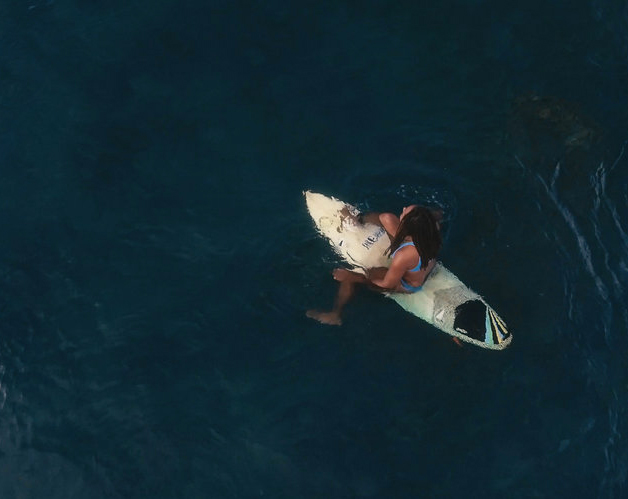

By mid-January, Jasmine Harrison, a swim instructor and bartender, had been alone at sea for nearly 50 days. She had rowed 1,600 miles through the ill-tempered Atlantic Ocean and was only halfway there.

If she could push forward a day at a time (or some 60 miles), Harrison, 21, of North East England, would become the youngest woman to row an ocean, beating an American, Katie Spotz, who held the title since 2010.

After 70 days 3 hours 48 minutes, she rounded the bend into English Harbour, on the southern coast of the Caribbean island of Antigua, around 10 a.m. local time on Saturday morning. This year, because of coronavirus restrictions, there were few boats there to welcome her after two months of paddling, 12 hours a day.

Her award for completing the Talisker Whisky Atlantic Challenge, ocean rowing’s most prestigious challenge? A vinyl banner that read, “New World Record.” (The winners were given $6,000 Bremont watches.)

🏆 RUDDERLY MAD FINISHES TWAC2020 + NEW WORLD RECORD🏆

— World's Toughest Row (@toughestrow) February 20, 2021

21 year old Jasmine Harrison of @rudderlymad has completed the @TaliskerWhisky Atlantic Challenge in 70 days, 3 hours, 48 minutes, breaking the WORLD RECORD for the youngest female to row solo across any ocean!#TWAC2020 pic.twitter.com/ktMNgEu7gm

The obscure endurance sport has gained traction in recent years, and Harrison joined a growing number of rowers from diverse backgrounds and skill levels who attempted the extreme feat.

Since a pair of Norwegians successfully rowed from Manhattan to France in 1896, there have been about 900 attempts to row an ocean. Only two-thirds have been successful. To put that in perspective, 955 people attempted to summit Mount Everest in 2019 alone.

It’s not a sport for the faint of heart. Harrison’s 550-pound boat was twice toppled by rogue waves, sending her into the water. The second time, she injured an elbow. She had frightening close calls, including nearly colliding with a drilling ship at four in the morning. She missed her family and her dogs and cold drinking water. She also missed music. Her speaker, which had the English rock band the Wombats and Rachel Platten’s “Fight Song” on repeat, had fallen into the water.

Every December, the Atlantic Challenge sends rowers — from solo rowers to teams of twos through fives — across 3,000 miles of ocean, from the Canary Islands, off the northwest coast of Africa, to Antigua and Barbuda.

Paddling some 20,000 strokes a day demands a particular style of determination.

“It’s not a rational or sensible thing to do,” said Roz Savage, the English rower who in 2006 became the first women’s solo competitor to enter and finish the race. “It’s something that comes from the heart, not from the head.”

Savage sits atop ocean rowing’s most elite subset: female single-handers, or solo rowers. Fewer than 200 women have successfully rowed an ocean, and only 18 have made it across the Atlantic solo. Savage is the only one to have successfully crossed three — the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Indian.

Savage, like Harrison, had little rowing experience when she entered the event.

Harrison just happened to be in Antigua in 2018, after traveling to the Caribbean to teach swimming and volunteer with Hurricane Maria relief efforts. She was at a bar in Nelson’s Dockyard, where the race finished, and struck up a conversation with a relative of an Atlantic Challenge rower who was about to finish. “Hearing about the race just took me,” she said.

Some of the earliest ocean rowers have been women, but the sport remains overwhelmingly male. “When I started, women in exploration was something that was a little frowned on,” said Tori Murden McClure, who in 1999 became the first woman, and American, to row the Atlantic solo. “I certainly experienced lots of sexist things.”

Before the arrival of Atlantic Campaigns, which took over management of the challenge in 2013, the race’s organizers had cultivated rowers who “tended to be white, British and male,” said the challenge’s head safety officer, Ian Couch, who has rowed both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. “It was a bit of a club, a very much closed shop.”

The paradigm is now shifting. In 2016, four women entered the event; this year, there were 20, almost half of the event’s roster. Next year’s contingent of 24 women will be the largest the race has had.

Atlantic Campaigns has pushed to expand the race beyond its British roots, which has been crucial to the sport’s growing inclusivity. But having women like Savage and McClure shatter the image of the traditional explorer has mattered the most. “There was a time not long ago when doing an Ironman was considered crazy,” McClure said. “It’s what we think of as possible that shifts.”

The Atlantic Challenge is also beginning, albeit slowly, to reflect the racial diversity you would expect from a race organization whose staff of 21 represents 10 nationalities, and an endurance event that straddles an eighth of the globe.

In the 2019 event, the Antiguans Christal Clashing, Kevinia Francis, Elvira Bell and Samara Emmanuel became the first Black team — male or female — to complete the race. To date, the Atlantic Challenge has had seven Black competitors, including the Antiguan women.

“Being able to do a journey like that allowed us to write our own story, to take control of the narrative that Black people don’t swim, they don’t do these kinds of activities,” Clashing said. “In the end, we were able to say, ‘Yes, there was a cultural trauma that occurred for us across the Atlantic Ocean, but we are not allowing that to dictate what we do anymore.’”

This year’s race included athletes from Spain and South Africa, Antigua and Uruguay, the United States and Britain, among others. At a time when many sporting events were drastically changed or put on hold, the race — one of the world’s most socially distant — was able to move forward.

As Harrison approached her final weeks of the journey, the weather remained calm and the surface of the water shook out into “the brightest turquoise you’ve ever seen,” she said over satellite phone on Feb. 12. A pod of Risso’s dolphins followed her for hours. A blue whale rolled beside her, the white, molar-like edge of its flipper nearly high-fiving her oar.