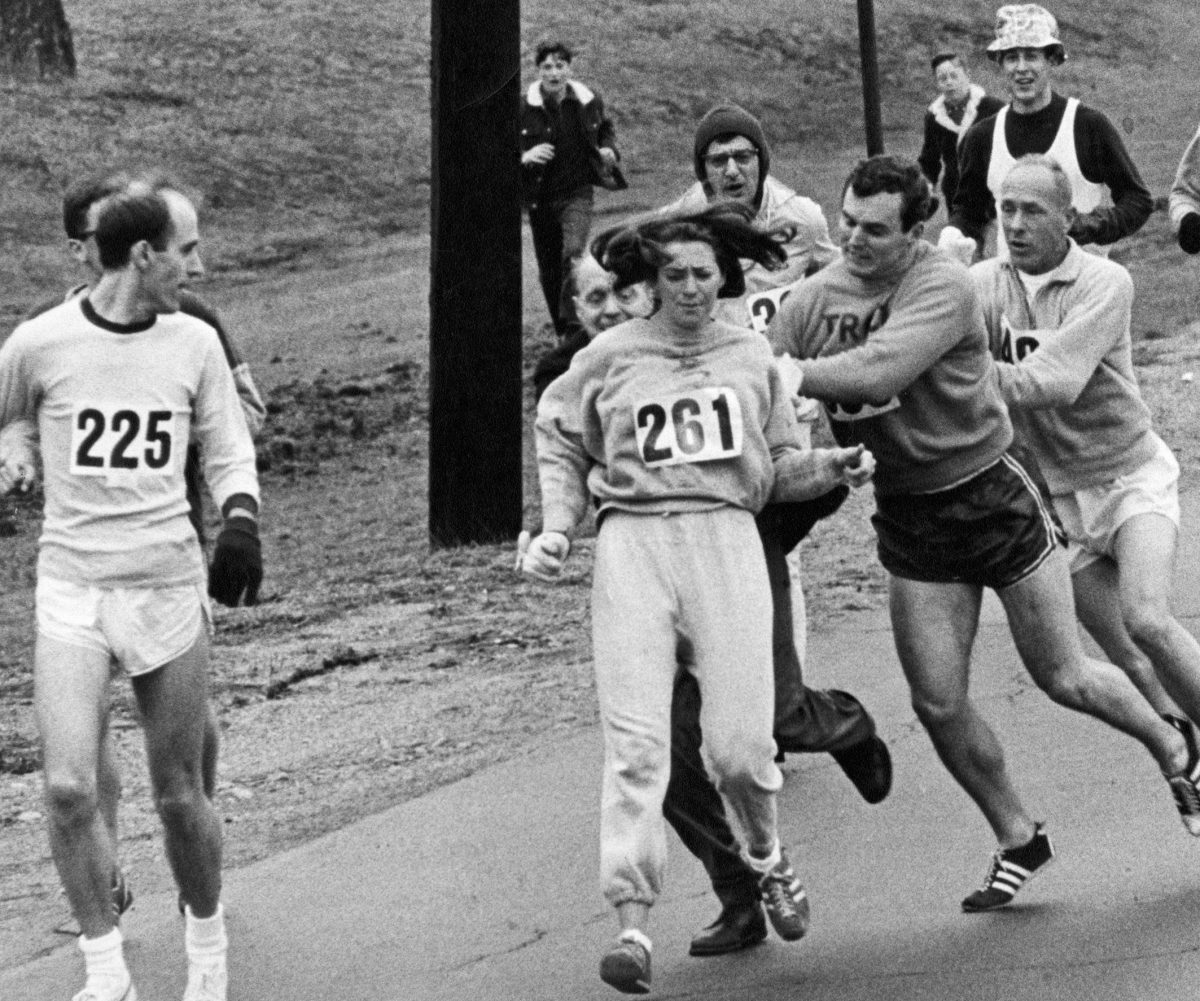

Dick, Kerr Ladies from the 1920-21 season CREDIT: Getty Images/Popperfoto

It was Boxing Day, 1920 and 53,000 spectators were packed inside Goodison Park for the big game of the festive football calendar. There was so much fervour surrounding the match, as hordes of fans flocked across Stanley Park, that as many as 15,000 more people were said to have been turned away outside.

But they were not there to watch 22 men kick a leather ball around. In fact, this was a women’s football match.

The stars of the show were Dick, Kerr Ladies FC, a team made up of World War One munitions factory workers from Preston, who had started playing football in 1917 to raise money for hospitalised soldiers.

They had played their first game on Christmas Day, 1917, when 10,000 spectators watched them at Preston’s Deepdale. They wore black and white striped jerseys, sky blue shorts and black and white socks, plus hats – deemed compulsory at the time because of their long hair.

By 1920, after enjoying an unbeaten tour in France that boosted their publicity and popularity, they were used to attracting much larger audiences.

Speaking to The Game Changers podcast, Gail Newsham, the author of ‘In a League of their Own’ which tells the story Dick, Kerr Ladies, said: “Women’s football was growing up and down the country during the [First World] war, with the male league program suspended. Women were playing football as part of the war effort to raise money for people affected by the war.

“Dick, Kerr Ladies [initially] raised money for the soldiers of the local hospital, Preston’s Moor Park Military Hospital. The team grew from strength to strength, playing most of the home games at Preston North End.”

Newsham, 67, was a two-time Women’s FA Cup semi-finalist in her own playing career with Preston Rangers, who are now known as AFC Fylde Women. Her love affair with the story of Dick, Kerr Ladies began with a 1992 reunion and she has dedicated much of her life to their story ever since. The more information she gathered regarding the team, the clearer it became that they had raised a remarkable amount of money for charity.

“It would be in excess of £10 million in today’s money,” Newsham added. “Some of the girls lost their own brothers [in the war]. It must have been so hard for them and they wanted to give something back in any way that they could.”

Yet Dick, Kerr Ladies were not merely fundraisers. By all accounts, they were exceptional footballers, playing at a time when the women’s game was thriving.

Winger Lily Parr became an icon. Described as a chain-smoker with a lethal left foot and a “kick like a mule”, she had been just 14 years old when she began playing for the team. She would become one of the sport’s top goal-scorers and was credited with scoring five times in a single international game against France in a 5-1 win in 1921.

She is estimated by Fifa to have scored over 900 goals before she retired, aged 45, while other reports state she netted more than 1,000 times. The National Football Museum in Manchester is set to open a gallery dedicated to her life in spring 2021.

Of course, Parr was not the only star name. Defender Alice Kell, Dick, Kerr Ladies’ first captain, also developed a fine reputation across the sport. Centre-forward Florrie Redford scored a reported 170 goals for the club, with Redford and 4ft 10in Jenny Harris scoring in England’s first recorded international against France.

Dick, Kerr Ladies, whose name related to the business that owned that factory in which the players worked – Dick, Kerr and company – were said by their manager, Alfred Frankland, in 1937, to have played 437 matches, winning 424 and losing just seven, while scoring 2,863 goals.

Their attendance of 53,000 for their Boxing Day fixture at Goodison – which saw them win 4-0 against St Helens Ladies – would make a significant mark in the history books, setting a British record for a women’s football crowd.

It remained the largest crowd for a women’s game in England for nearly 92 years, not being eclipsed on UK soil until 70,584 people saw Great Britain beat Brazil 1-0 at Wembley during the London 2012 Olympics.

In the modern era, Women’s FA Cup finals at England’s national stadium are used to large turnouts, but even the cup’s competition-record crowd of 45,423, from Chelsea’s victory over Arsenal in May, 2018, is no match for the masses that gathered on Merseyside to see Dick, Kerr Ladies.

Similarly, no Women’s Super League crowd has yet come close – the WSL’s best single attendance so far saw 38,262 watch a north London derby last year.

That begs the question: How did Dick, Kerr Ladies bring in such large crowds 100 years ago, with the kind of fanbase that most clubs in the modern, professional era – male or female – can only dream of?

Most critically, a monumental turning point came in the following December, when a decision was taken by the Football Association that would change the course of women’s football forever.

Just under a year after that famous match on Merseyside, the FA banned women’s football matches from being played on FA pitches.

It was a ban that would last 50 years until 1971 and undoubtedly stunted the growth of the sport, to say the least. Those behind the decision claimed that football was “quite unsuitable for females”. They cited potential impacts to women’s fertility if they were injured during play.

Dick, Kerr Ladies and many other women’s team’s played on, defying the ban, but landmark games at grounds like Goodison had been outlawed and, playing predominantly at more recreational facilities, crowds did not return on anywhere near the same scale.

“For 50 years women’s football was then in the wilderness,” Newsham continued. “In my opinion, the Goodison match was the turning point, really. Throughout 1921, there was trouble brewing and there were people questioning it [women’s football] and all the money involved. ‘Was it going to the right places?’ The FA made it increasingly more difficult for clubs to let them use the grounds.

“They couldn’t have all these spectators going to watch women’s football because they needed them to populate the men’s games. [Now] we’ve still got a bit of catching up to do.”