When Alison Hargreaves reached the peak of Mount Everest on May 13, 1995, she sent a radio message to her son and daughter: “To Tom and Kate, my dear children, I am on the highest point of the world, and I love you dearly.”

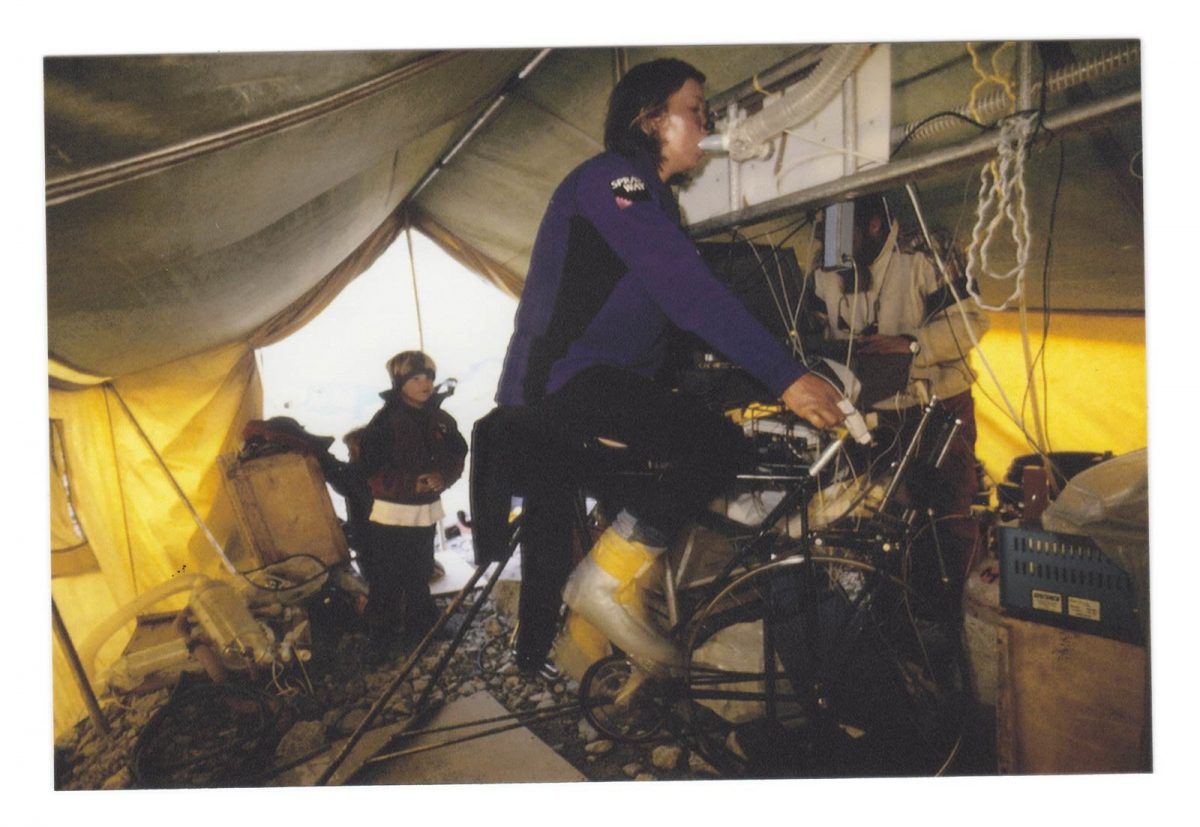

With that triumph, she became the first woman in history to conquer the Earth’s apex — 29,029 feet high — alone and without bottled oxygen. Hargreaves, one of the world’s greatest alpinists then and of all time, also did without the fixed ropes set by others on that Himalayan climb. Only the Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner had ascended Everest in a similar manner before.

Her homeland, Britain — stoked by a front-page headline in The Times of London that read “One of the greatest climbs in history” — rejoiced.

“The rest of Fleet Street followed, keeping the story in the air” until her return, her daughter, Kate Ballard, said in January.

The celebrations were “just unbelievable,” Hargreaves recalled in what is thought to be her last interview. “These guys were leaping all over me and the trolley, trying to take pictures,” she said of the photographers who awaited her at Heathrow Airport in London. “It was just frantic.”

But the excitement did not last long. Exactly three months after Everest, in the late afternoon of Aug. 13, Hargreaves reached the summit of K2 in Pakistan, the world’s second-highest peak. Just hours later, she and five others died when they were engulfed by a storm with fierce winds that rose up the mountain. She was 33.

After her death, a backlash — fueled by a media frenzy around her death — began to mount. Some called her selfish and criticized the choice to leave behind young children to put herself in harm’s way. Similar denunciations were not leveled so harshly against the fathers who died on the mountain alongside her.

“The media wheeled out the psychologists who asked why I didn’t break down,” Hargreaves’s husband, James Ballard, said in a 2002 interview with The Guardian. “The next stage was everyone saying she shouldn’t have left the children.”

Those who criticized Hargreaves were “wrong and incredibly shortsighted,” her daughter said. “Twenty years later with more equality and thinner glass ceilings, would they have written the same? No.”

Editors’ PicksHow Ronald Reagan TriumphedTrying to Make It Big Online? Getting Signed Isn’t EverythingShhh! We’re Heading Off on Vacation

In the 2002 interview, James Ballard expressed disappointment in how women and mothers are judged for succeeding in their careers, particularly dangerous ones. “How could I have stopped her?” he said of his wife. “I loved Alison because she wanted to climb the highest peak her skills would allow her to. That’s who she was.”

“I just hope that there was a point to Alison’s death and that, in the long term, what she achieved will help shift attitudes,” he said.

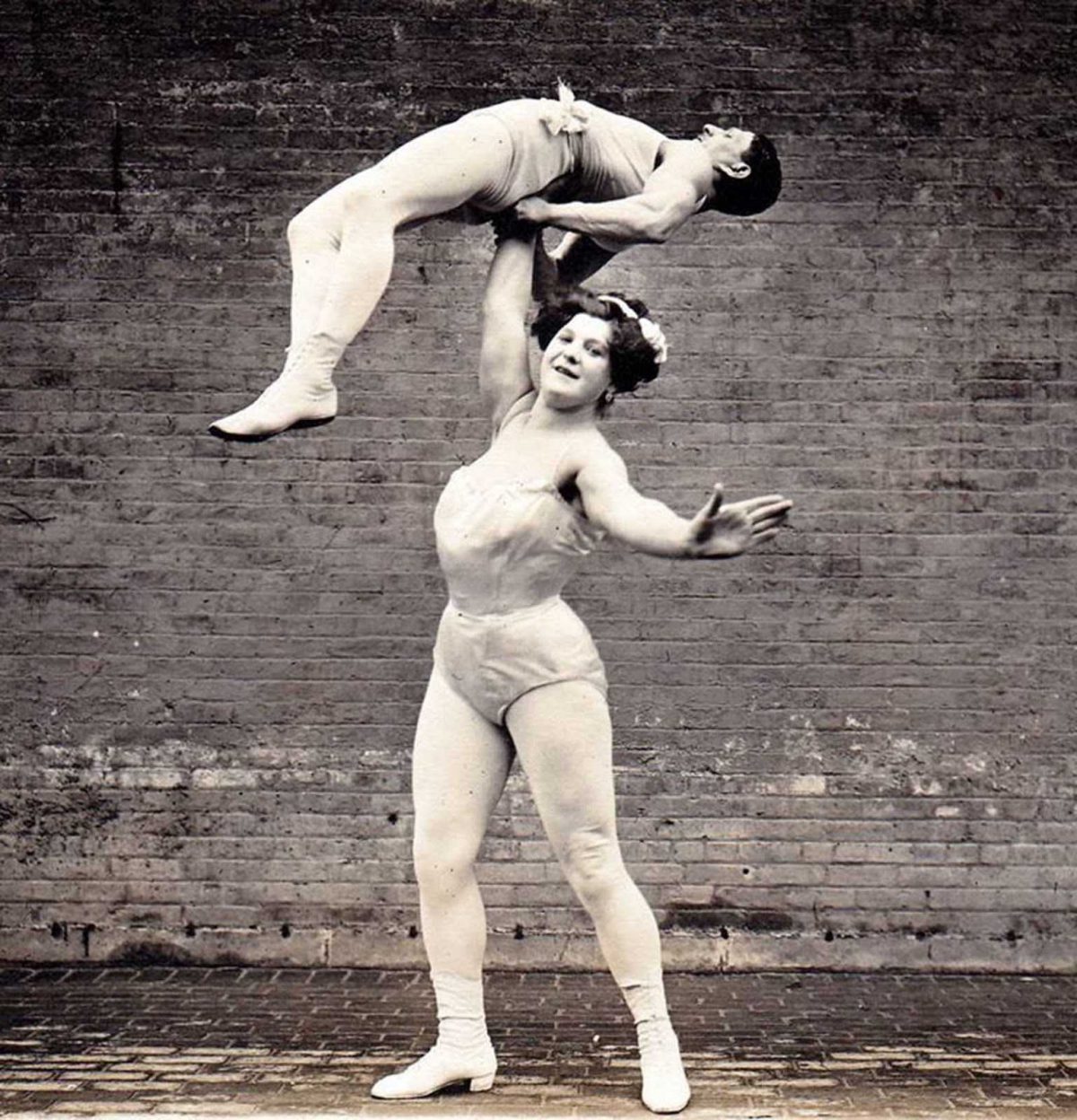

Some would say she did just that. Hargreaves was a “trailblazer,” Molly Schiot, who profiled Hargreaves in her 2016 book, “Game Changers: The Unsung Heroines of Sports History,” told the online magazine Oxy last year.

Her courageous Everest climb helped in “breaking down social constructs of what it means to be a mom,” Schiot said.

On July 28, 2017, the mountaineer Vanessa O’Brien conquered K2, becoming the first American woman to do so. (She also holds a British passport.) And at 52, O’Brien was also the oldest woman to reach the peak.

Two days later, on July 30, she paid tribute to Hargreaves in a Twitter post. “I respect & acknowledge Julie Tullis (1986) & Alison Hargreaves (1995) who lost their lives on descent of #K2 – I thought of them often #RIP,” she wrote. Tullis, a British climber, died during a storm while descending K2.

In her final interview, Hargreaves, who began rock climbing at 13, said that Everest was “always at the back of my mind.”

“It was never, ever at the front of it,” she continued. But that changed when she started considering the prospect of taking it on alone: “I’d started to do a lot of solo climbing and then thought it would be great to try and do Everest totally independently, totally under my own steam, without oxygen.”

Everest was not her only record. In the summer of 1993, Hargreaves became the first person to climb the notoriously perilous six great north faces of the Alps solo in a single season. The undertaking inspired her book, “A Hard Day’s Summer.”

In 2015, her son, Tom Ballard, who was 6 years old when she died, became the first person to climb the north faces alone in a winter season. Her daughter is also a mountaineer.

In a way, Tom’s first Alps ascent was with his mother. In July 1988, Hargreaves scaled the treacherous north face of Eiger while six months pregnant with him. The trek was to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first ascent of Eiger.

In her last interview, Hargreaves addressed the challenges and inequality female mountaineers faced. The interview was conducted on July 27, 1995, at K2’s base camp by Matt Comeskey, a fellow climber who went on to survive the storm after turning back early. It was obtained by The Independent, and published that September.

“I think women climb before they get married, before they have boyfriends and babies, then they lose interest,” Hargreaves told Comeskey. “Having children is very fulfilling, and a lot of people don’t feel the need for anything else.”

“For me, that was a conscious decision,” she said. “I actually wanted children, and I also wanted to carry on with the climbing.”

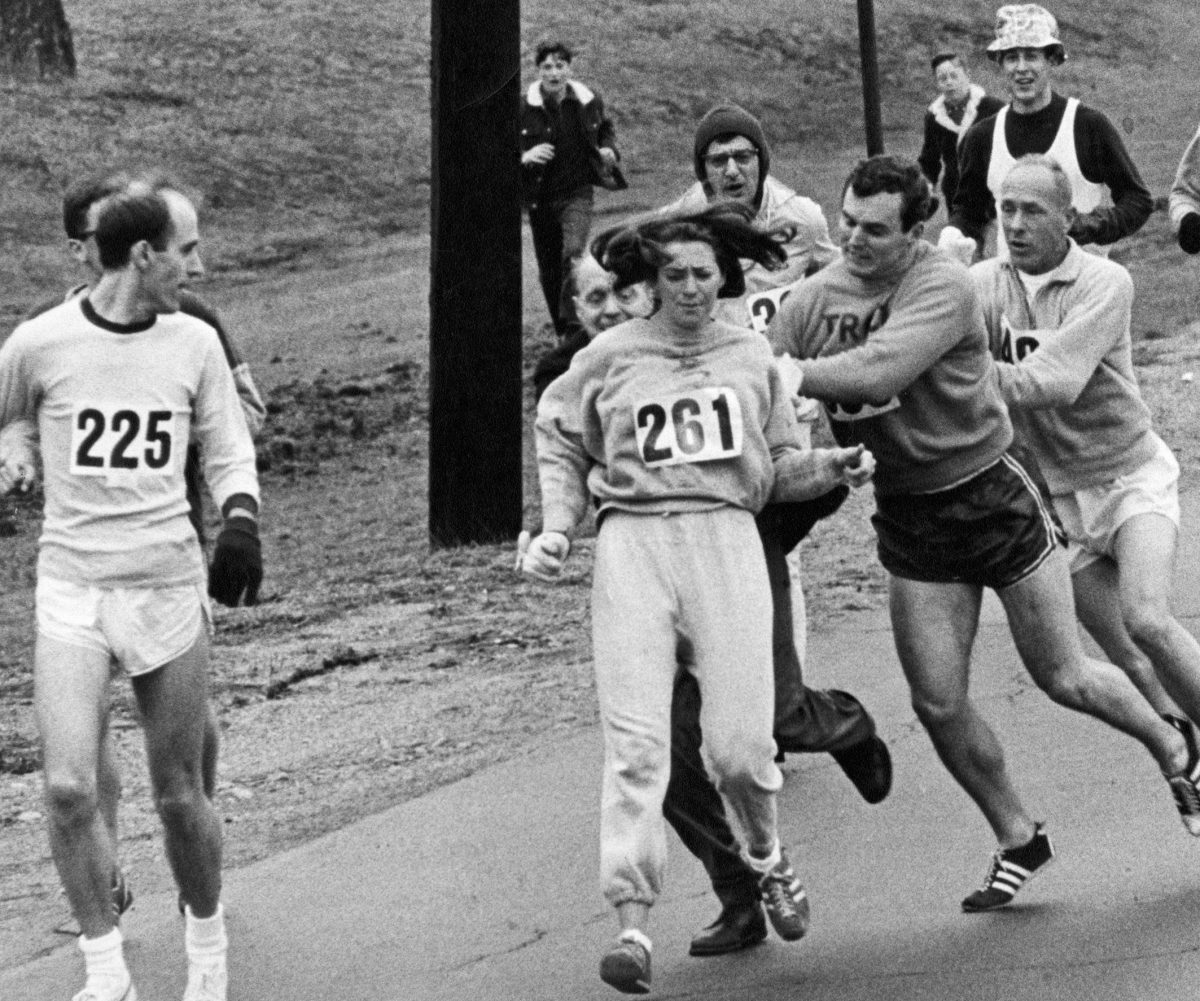

When asked if a female climber needed to be tougher than a man, she said: “I think that women in general have to work harder in a man’s world to achieve recognition.”

She recalled an exchange in which she was diminished by a colleague. “I was at a climbing dinner once when a very well-known climber came up to me and said: ‘Are you a roadie?’” she said. “For me, that was the worst thing he could have said.”

“I’ve always had a chip on my shoulder, I’m sure,” she said.

Alison Jane Hargreaves was born on Feb. 17, 1962, in Derby, England. She was the second of three children of John Edward Hargreaves, a senior scientific officer at British Rail Derby, and Joyce Winifred Hargreaves, born Carlisle.

She was survived by her mother and father; her husband; her two children; her sister, Susan, and brother, Richard. Her father has since died.

At 28,251 feet, K2 in the Karakoram Range of Pakistan is just under the height of Everest but is regarded as far more demanding and dangerous. Hargreaves was a member of an American expedition led by Rob Slater. Also on the mountain was a team from Spain and a New Zealand expedition led by Peter Edmund Hillary, son of Sir Edmund Hillary, the first man to conquer Everest.

Extreme weather sent most of the climbers back before reaching the top, including Hillary and some members of his team, like Comeskey. But Hargreaves and Slater teamed up with Bruce Grant and Jeff Lakes from the New Zealand group, and the Spaniards Javier Escartin, Javier Olivar and Lorenzo Ortiz for another try. It would prove fatal.

All but Lakes, who had turned back, reached the summit. Hargreaves did so without artificial oxygen. Lakes died from exposure on his descent.

Hargreaves had intended to attempt the third-highest peak in the world, Kanchenjunga in the Himalayas, next.

“If you are given two options, take the harder one because you’ll regret it if you don’t,” Hargreaves said in her final interview. “At least if you take the harder one and fail, you’ll have tried.”